After spending six weeks in Ruby land, last week was all JavaScript all the time at The Flatiron School. I feel like I’ve just added a hammer with superpowers to my programming tool box. You might bend a few nails along the way, but you can build almost anything with it.

Also, JavaScript is weird. Although it cares a lot about semi-colons, there are some important ways in which, just like the honey badger, it just doesn’t seem to care at all. Here I will attempt to get comfortable with this strange new animal by diving deep into some of its more surprising aspects. To provide some contrast and context, especially for those who (like myself) are more at home with Ruby, I’ll make some comparisons as I go along.

Scope

Let’s dive right in. For comparison, here is some Ruby:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

In Ruby, a method is a scope gate, so dog is not defined in the bark method. Ruby will tell you this in no uncertain terms:

1 2 3 4 | |

On line 4, Ruby has no idea about what dog is, because the universe in line 4 is the local scope of the method bark. This scope gate can be very nice, since it means we cannot accidentally overwrite a variable we defined in the global scope from within a method. In order to make dog into a global variable that we can access inside the method, Ruby requires us to be very explicit about it, putting a $ in front of that variable both where it is defined and wherever it is referenced:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Now we clearly see that we are playing with a global variable, and Ruby plays along:

1 2 3 | |

While JavaScript does have a concept of functions creating a new scope, variables assigned outside of those functions can easily be accessed from within:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

JavaScript doesn’t care if you want to reach outside the function’s scope to grab a variable. JavaScript functions have knowledge of the universe around them:

1 2 3 | |

So what else can you do with a variable defined outside a function from within a function? As it turns out, JavaScript will let you do whatever you want:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

What happened to Fido?

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Looks like the name change was permanent. And by the way, by always using var, we can prevent such dangers:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

By using var within the function, we created an entirely different dog and did not alter the original.

Arity Schmarity

Before we go any further, I must admit that hadn’t heard the word arity until I crossed paths with JavaScript. I reckon I’m not alone in this, so here’s a definition courtesy of Wikipedia:

In logic, mathematics, and computer science, the arity of a function or operation is the number of arguments or operands the function or operation accepts.

OK. This sounds like something I know from Ruby land. Here’s a familiar example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

According to the above definition, the initialize method of the Dog class takes exactly one argument. You could say its arity is one (more commonly, this is known as a unary function).

Ruby cares about arity, and will give you very nice error messages to make you aware of this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

I tried to make a new Dog with 0 arguments, and Ruby was expecting 1. So Ruby blew up. This is arity checking at work.

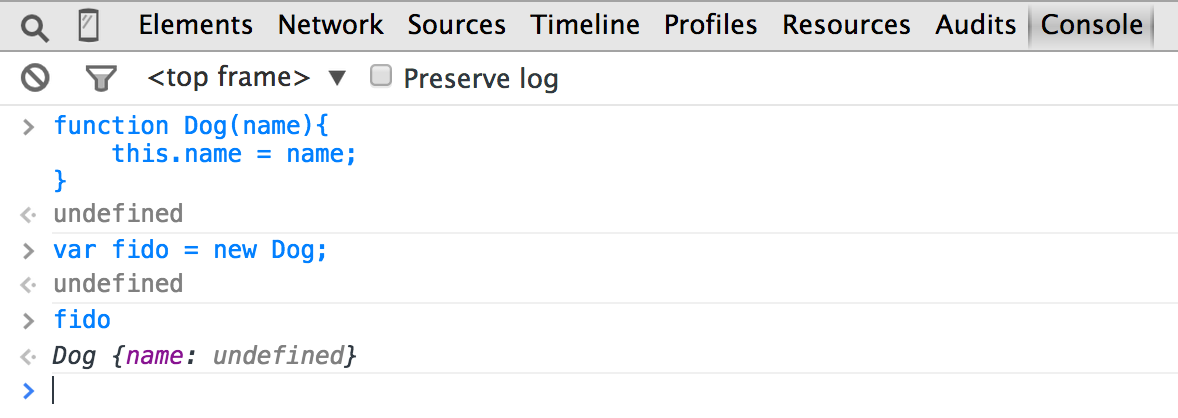

JavaScript does not care about arity! Here’s photographic proof (this is a lot easier to see in the browser’s JavaScript console):

To review what just happened:

- I made a constructor function for

Dog(yeah, functions are really all-purpose in JavaScript, so that right there was a class definition of sorts). - In this constructor function, I said that

Dogtakes aname. - I made a new

Dog,fido, and did not pass in any arguments. - JavaScript did not blow up.

- Just to be sure, I asked JavaScript to show me

fido. - JavaScript returned a

Dogobject with anameofundefined.

Whenever it can, JavaScript will try to help you out, whether you want it to or not. If you say a Dog has a name and then forget to give it one, JavaScript will trust that this was your intent and will throw in an undefined rather than yelling at you.

Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks

Ruby cares about defining an object’s attributes and behaviors up front. Objects in Ruby behave in consistent and predicatable ways.

Using our prior definition of the Dog class, Ruby will let us know that we haven’t taught Dogs to bark yet:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

Of course! We did not define a bark method, so we get a predictable NoMethodError.

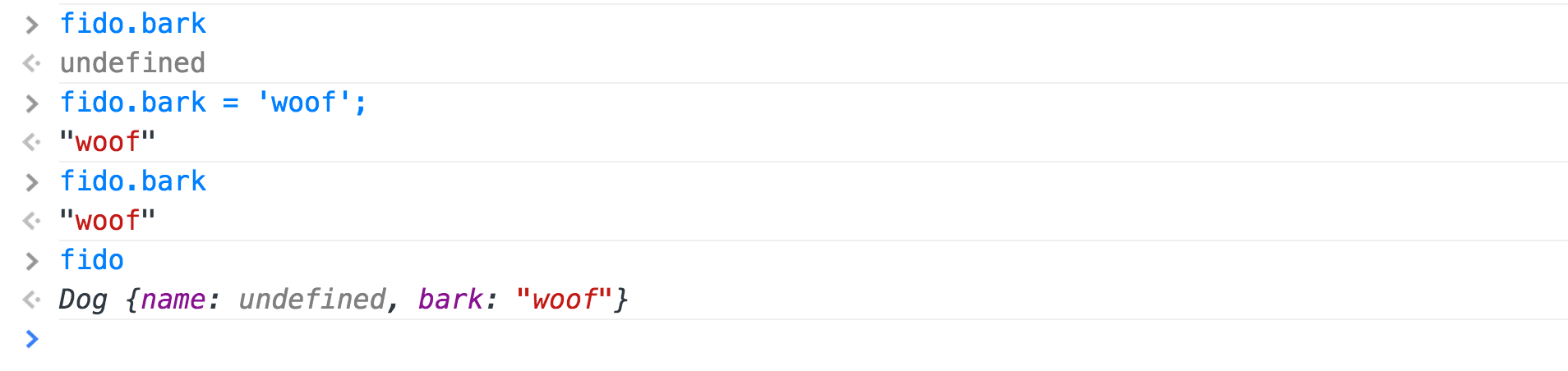

JavaScript doesn’t care about defining all of an object’s attributes and behaviors up front, and pretty much lets you do whatever you want, whenever you want. Here’s a continuation of the console session above:

- I asked

fidoto bark, having never defined abarkfunction or attribute. JavaScript quietly returnedundefined. - I told JavaScript to give

fido.barkthe value of'woof', and JavaScript happily obliged. - Now not only can

fidobark, but theDogobject that isfidohas been fundamentally altered, now containing a newbarkattribute!

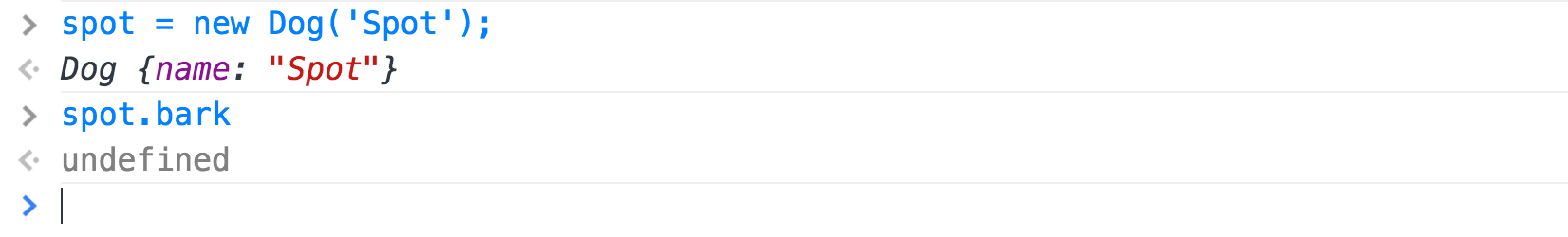

So, can all Dogs bark now?

No, they cannot. Now the definition of Dog is a bit of a mess - fido is a Dog that can bark, while spot can’t. The very nature of Dog-ness has been brought into question, and JavaScript is fine with all of this. No errors, no complaining. For better or for worse.

Playing with Global Scope

This one is extra weird, so get ready.

In the hierarchy of Ruby objects, main is the top level:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

I don’t know why you’d want to mess with main, and Ruby makes certain it’s not easy to do so (in fact, it’s impossible to do so by accident):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Want to mess with the top-level object in JavaScript? Go right ahead, JavaScript doesn’t care!

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

I just named the global object after myself, and JavaScript did not care one bit. This example is a bit contrived, but believe me that some undesireable things can happen if you don’t watch out for global assignment. Here’s a (slightly) less contrived example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 | |

If I run this code, here’s what my debug statements reveal:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

As you can see, Bad Things can happen when the global object is always available. Fortunately, there is a way for you to make JavaScript care about this! You just have to tell JavaScript to use strict.

1 2 3 4 | |

Now, when we run the code, JavaScript will blow up just the way we want it to!

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

The Moral of the Story

This was a long post, and it probably could get longer. But I think this is enough to chew on for now. The bottom line is that JavaScript has some crazy ways, but these ways are not unlearnable, and the reward for learning them is a much saner coding experience. If you understand the quirks, remember your vars, and always use strict, you and JavaScript can be unstoppable, just like the honey badger.